Tradition is not the worship of ashes, but the preservation of fire.—Gustav Mahler

Showing posts with label Alexander Hamilton. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Alexander Hamilton. Show all posts

Tuesday, October 17, 2017

Tillman and Blackman make the rubble bounce on the emoluments clause

Continuing their exposition of the emoluments clause and its inapplicability to President Trump and his business dealings, this blog's very own Prof. Seth Barrett Tillman and his co-author Prof. Josh Blackman have published this piece over at The Wall Street Journal online: The 'Resistance' vs. George Washington. Unfortunately, their article is behind the WSJ's paywall, but an excerpt can he read over at Instapundit, available here. Worth reading!

Thursday, October 12, 2017

Alexander Hamilton & William Blackstone on the nature of government

One of the often overlooked documents leading up to the American Revolution is The Farmer Refuted, written in 1775 by a young Alexander Hamilton. One of a number of critical works that set the stage for American independence, Hamilton's treatise set forth in very clear terms much of the intellectual foundation to justify the colonists' move to defend their rights against incursions by the British government.

While not an explicit call for independence, The Farmer Refuted is an excellent statement of the principles that would eventually lead the Americans to declare their separation from the British Empire. The core of Hamilton's argument in The Farmer Refuted centers around divinely-given natural law as the core of human obligation to one another. This natural law, since it comes from God, is not dependent on human government or human institutions for its validity, but instead stands as judge over human laws and customs.

Hamilton cites as his authority for this point not the Bible or any of the classical or scholastic writers who discuss natural law, but rather William Blackstone, the great compiler of the principles of English law. He does this, of course, to ground his point in the firm soil of the English Constitution -- to demonstrate that his point is not some radical notion but rather is part of the traditional approach to law and morality that sustained the British Empire itself.

The natural law defends the rights of Americans as much as the rights of Englishmen because, as Hamilton quotes Blackstone, "It is binding over all the globe, in all countries, and at all times."

After his citation of Blackstone, young Hamilton then began to build an argument about the nature of government. Since God creates human beings and sustained them, the rights of human beings are dependent upon God's natural law. Understood by reason, which is itself a gift of the Creator, natural law allows human beings to "discern and pursue such things as were consistent with [their] duty and interest." Critically, natural law gives to each person "an inviolable right to personal liberty and personal safety." In the absence of government, no person has the right "to deprive another of his life, limbs, property, or liberty," or to command another person under obedience.

Striking directly at the British claim to be able to govern by right other than consent, Hamilton then applies these principles to the notion of government's origin. "[T]he origin of all civil government, justly established," Hamilton proclaims, "must be a voluntary compact between the rulers and the ruled." In such a compact, the power of government is limited in order to secure the "absolute rights" of the people. No pedigree can substitute for the consent of the governed, "what original title can any man, or set of men, have to govern others, except for their own consent?" To assume such power, "to usurp domination," is to break God's natural law, and thus renders such an assumption invalid. The people have, in Hamilton's words, "no obligation to obedience" in such a situation.

Hamilton concludes this portion of his argument with another quote from Blackstone, book-ending, as it were, his position on the necessity of consent of the governed with the authority of the great expositor of the English legal system. The principal aim of society is to protect individuals in the enjoyment of those absolute rights which were vested in them by the immutable laws of nature, but which could not be preserved in peace without that mutual assistance and intercourse which is gained by the institution of friendly and social communities. Hence it follows, that the first and primary end of human laws is to maintain and regulate these absolute rights of individuals.

With that, Hamilton expressed in detail the fundamental principles about God, natural law and government by consent that would later be used by Jefferson at the beginning of the Declaration of Independence. While Jefferson's formulation of those principles is well-known, Hamilton's earlier, more precise and grounded formulation of those same principles in The Farmer Refuted deserves greater appreciation by Americans and all those concerned with human liberty and limited government.

While not an explicit call for independence, The Farmer Refuted is an excellent statement of the principles that would eventually lead the Americans to declare their separation from the British Empire. The core of Hamilton's argument in The Farmer Refuted centers around divinely-given natural law as the core of human obligation to one another. This natural law, since it comes from God, is not dependent on human government or human institutions for its validity, but instead stands as judge over human laws and customs.

Hamilton cites as his authority for this point not the Bible or any of the classical or scholastic writers who discuss natural law, but rather William Blackstone, the great compiler of the principles of English law. He does this, of course, to ground his point in the firm soil of the English Constitution -- to demonstrate that his point is not some radical notion but rather is part of the traditional approach to law and morality that sustained the British Empire itself.

Striking directly at the British claim to be able to govern by right other than consent, Hamilton then applies these principles to the notion of government's origin. "[T]he origin of all civil government, justly established," Hamilton proclaims, "must be a voluntary compact between the rulers and the ruled." In such a compact, the power of government is limited in order to secure the "absolute rights" of the people. No pedigree can substitute for the consent of the governed, "what original title can any man, or set of men, have to govern others, except for their own consent?" To assume such power, "to usurp domination," is to break God's natural law, and thus renders such an assumption invalid. The people have, in Hamilton's words, "no obligation to obedience" in such a situation.

Hamilton concludes this portion of his argument with another quote from Blackstone, book-ending, as it were, his position on the necessity of consent of the governed with the authority of the great expositor of the English legal system. The principal aim of society is to protect individuals in the enjoyment of those absolute rights which were vested in them by the immutable laws of nature, but which could not be preserved in peace without that mutual assistance and intercourse which is gained by the institution of friendly and social communities. Hence it follows, that the first and primary end of human laws is to maintain and regulate these absolute rights of individuals.

With that, Hamilton expressed in detail the fundamental principles about God, natural law and government by consent that would later be used by Jefferson at the beginning of the Declaration of Independence. While Jefferson's formulation of those principles is well-known, Hamilton's earlier, more precise and grounded formulation of those same principles in The Farmer Refuted deserves greater appreciation by Americans and all those concerned with human liberty and limited government.

Wednesday, October 11, 2017

Tillman and Blackman: bringing light to President Trump and the Constitution's emoluments clause

If you've been following NRC's Facebook page, you know that this blog's own Professor Seth Barrett Tillman has co-authored a series of posts with Professor Josh Blackman over at the Washington Post online detailing flaws in efforts to apply the emoluments clause of the Constitution to President Trump and his private business activities. Their work there is high-level constitutional and historical scholarship packaged to be accessible to a non-specialist audience. And it makes crystal clear that which so many of the leading "scholars" of constitutional law would rather have opaque.

Part 1 is here.

Part 2 is here.

Part 3 is here.

Part 4 is here.

Part 5 is here.

Professor Tillman took a lot of flack prior to publishing this series for his views on the emoluments clause and its applicability to President Trump. We won't go into that here, but here's a New York Times story about the controversy about Tillman's groundbreaking scholarship regarding the emoluments clause and its applicability to the president. His work with Professor Blackman is so definitive that his leading critics have issued formal apologies to him. Some of those apologies are online here and here.

Why is all this important? Because the emoluments clause is the basis of a lawsuit designed, ultimately, to pressure President Trump from office by targeting his businesses. The strategy targeting Trump's businesses is outlined in this post over at Instapundit. Tillman and Blackman have done yeoman's service in showing how weak the overall legal arguments against the president truly are.

Part 1 is here.

Part 2 is here.

Part 3 is here.

Part 4 is here.

Part 5 is here.

Professor Tillman took a lot of flack prior to publishing this series for his views on the emoluments clause and its applicability to President Trump. We won't go into that here, but here's a New York Times story about the controversy about Tillman's groundbreaking scholarship regarding the emoluments clause and its applicability to the president. His work with Professor Blackman is so definitive that his leading critics have issued formal apologies to him. Some of those apologies are online here and here.

Why is all this important? Because the emoluments clause is the basis of a lawsuit designed, ultimately, to pressure President Trump from office by targeting his businesses. The strategy targeting Trump's businesses is outlined in this post over at Instapundit. Tillman and Blackman have done yeoman's service in showing how weak the overall legal arguments against the president truly are.

Sunday, April 10, 2016

Alexander Hamilton's unorthodox conservative constitutional jurisprudence

Tom's post from yesterday evening got me thinking about the constitutional wisdom of Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton has long been overshadowed by many of the the major American founding fathers, largely because he had the misfortune of falling from political grace and then getting killed by Aaron Burr in a duEl. From such an end, knowledge of Hamilton quickly sank from popular culture, although thanks to the work of folks like Richard Brookheiser, Gordon Wood and Ron Chernow, he has finally received some of the attention from historical circles which he is due. And his story has even given rise to a popular Broadway musical exploring the themes and concepts of his amazing life.

In this post, I'd like to briefly look at Alexander Hamilton's contributions to the world of constitutional law—specifically, his approach to interpreting the Constitution as it developed between the Federalist Papers and his work as in both the Washington and Adams administrations. Hamilton is well-known for his defense of judicial review and the independence of the judiciary in the Federalist Papers. His arguments in favor of the power of the judiciary are part of his legacy as a legal thinker, and I won't take up space here simply repeating what others have already said. What bears closer inspection is Hamilton's approach to constitutional interpretation after the Constitution was ratified and during the time when he was in government.

As Forrest McDonald has noted, Hamilton's legal ideas were remarkably influential at the time, and "at least two of [Chief Justice John] Marshall's opinions were drawn directly from Hamilton's constitutional pronouncements." Hamilton advocated a flexible approach to constitutional interpretation, one that provided for a generous and expansive reading of federal power. It is no surprise that this kind of view closely paralleled his general political principles. But Hamilton also insisted that this expansive view of government power be limited by the Constitution's outline of government authority. Hamilton did not believe that the Constitution was simply a grant of general authority to the federal government; he was an enemy of the idea of a "living Constitution," of constitutional principles unmoored from the text of the Constitution itself. As he commented when discussing the power of the Congress to authorize corporations: "Whatever may have been the intention of the framers of a constitution, or of a law, that intention is to be sought for in the instrument itself, according to the usual & established rules of construction."

In addition, Hamilton contended that when discerning the intent of the Constitution's provisions, recourse outside of the text of the Constitution was to be avoided: "arguments drawn from extrinsic circumstances, regarding the intention of the convention, must be rejected."

Hamilton's approach to constitutional interpretation did not, therefore, reduce constitutional law to politics, nor was it an attempt to read the Constitution as an infinitely malleable text that would allow for the creation or recognition of new or novel rights. Hamilton believed that the Constitution's text was binding. He was, in effect, proponents of classic original intent jurisprudence, where the intentions of the Framers of the Constitution are sought by examining the actual text of the Constitution, rather than speculating on what the Framers might have meant, or by looking at extrinsic sources to supply the intent of the document.

Well, what about Hamilton's rather famous disagreement with Jefferson over the proper scope of federal authority under the Constitution? Hamilton's constitutional jurisprudence diverged from Jefferson's not over the question of original intent, but over the question of the explicit grant of authority to Congress under the Necessary and Proper Clause of the Constitution. Was the clause to be read expansively (as Hamilton and the Federalists advocated), or narrowly (as Jefferson and the early Democratic Republicans wanted)? Hamilton was convinced that it should be viewed expansively, in light of the Constitution's grant of enumerated powers to Congress. By the terms of the clause, Congress had the power to do what was "necessary and proper" to carry out its expressed powers. But in Hamilton's view, even this expansive reading of the Necessary and Proper Clause was still bracketed by the text of the Constitution itself.

Proof of this is seen in Hamilton's advocacy of the federal government improving the network of internal canals and roads within the United States in order to strengthen the country's domestic military defenses. Hamilton made this suggestion while serving, under President Adams, as the field commander of the federal army during the Quasi-War with France (1798-1800). An excessively expansive reading of the Necessary and Proper Clause, unhinged from the actual expressed powers of Congress, would see such internal defense improvements as being within Congress's overall military power with a possible connection to Congress's power to regulate interstate commerce. But that wasn't Hamilton's argument. Hamilton argued that Congress had the authority to establish the roads he proposed under its power to "establish post offices and post roads." But in order to have the authority to build canals, Hamilton argued, Congress would have to be empowered by a constitutional amendment.

That episode demonstrates the the constrained nature of Hamilton's way of reading of the Constitution. While committed to the idea of a flexible and vigorous federal government, Hamilton was also committed to the Constitution's function as a limitation on that government's power. When the text of the Constitution indicated that Congress had power, Hamilton urged that that power be used to its utmost. But when the text indicated that Congress did not have a given power, Hamilton insisted that the text be followed, even if he thought the text should be changed in order to facilitate better policy. This approach sets Hamilton clearly within the conservative camp when it comes to interpreting the Constitution -- as in his general approach to law & government, he would be an unorthodox conservative today, but a conservative nonetheless. Constitutional structure & constitutional language both mattered to Hamilton. And it is in both that he found the best guarantees against an overly expansive sweep of government power.

(Tom's post immediately below demonstrates this point as well in reference to the Senate's role in judicial appointments.)

In this post, I'd like to briefly look at Alexander Hamilton's contributions to the world of constitutional law—specifically, his approach to interpreting the Constitution as it developed between the Federalist Papers and his work as in both the Washington and Adams administrations. Hamilton is well-known for his defense of judicial review and the independence of the judiciary in the Federalist Papers. His arguments in favor of the power of the judiciary are part of his legacy as a legal thinker, and I won't take up space here simply repeating what others have already said. What bears closer inspection is Hamilton's approach to constitutional interpretation after the Constitution was ratified and during the time when he was in government.

As Forrest McDonald has noted, Hamilton's legal ideas were remarkably influential at the time, and "at least two of [Chief Justice John] Marshall's opinions were drawn directly from Hamilton's constitutional pronouncements." Hamilton advocated a flexible approach to constitutional interpretation, one that provided for a generous and expansive reading of federal power. It is no surprise that this kind of view closely paralleled his general political principles. But Hamilton also insisted that this expansive view of government power be limited by the Constitution's outline of government authority. Hamilton did not believe that the Constitution was simply a grant of general authority to the federal government; he was an enemy of the idea of a "living Constitution," of constitutional principles unmoored from the text of the Constitution itself. As he commented when discussing the power of the Congress to authorize corporations: "Whatever may have been the intention of the framers of a constitution, or of a law, that intention is to be sought for in the instrument itself, according to the usual & established rules of construction."

In addition, Hamilton contended that when discerning the intent of the Constitution's provisions, recourse outside of the text of the Constitution was to be avoided: "arguments drawn from extrinsic circumstances, regarding the intention of the convention, must be rejected."

Hamilton's approach to constitutional interpretation did not, therefore, reduce constitutional law to politics, nor was it an attempt to read the Constitution as an infinitely malleable text that would allow for the creation or recognition of new or novel rights. Hamilton believed that the Constitution's text was binding. He was, in effect, proponents of classic original intent jurisprudence, where the intentions of the Framers of the Constitution are sought by examining the actual text of the Constitution, rather than speculating on what the Framers might have meant, or by looking at extrinsic sources to supply the intent of the document.

Well, what about Hamilton's rather famous disagreement with Jefferson over the proper scope of federal authority under the Constitution? Hamilton's constitutional jurisprudence diverged from Jefferson's not over the question of original intent, but over the question of the explicit grant of authority to Congress under the Necessary and Proper Clause of the Constitution. Was the clause to be read expansively (as Hamilton and the Federalists advocated), or narrowly (as Jefferson and the early Democratic Republicans wanted)? Hamilton was convinced that it should be viewed expansively, in light of the Constitution's grant of enumerated powers to Congress. By the terms of the clause, Congress had the power to do what was "necessary and proper" to carry out its expressed powers. But in Hamilton's view, even this expansive reading of the Necessary and Proper Clause was still bracketed by the text of the Constitution itself.

Proof of this is seen in Hamilton's advocacy of the federal government improving the network of internal canals and roads within the United States in order to strengthen the country's domestic military defenses. Hamilton made this suggestion while serving, under President Adams, as the field commander of the federal army during the Quasi-War with France (1798-1800). An excessively expansive reading of the Necessary and Proper Clause, unhinged from the actual expressed powers of Congress, would see such internal defense improvements as being within Congress's overall military power with a possible connection to Congress's power to regulate interstate commerce. But that wasn't Hamilton's argument. Hamilton argued that Congress had the authority to establish the roads he proposed under its power to "establish post offices and post roads." But in order to have the authority to build canals, Hamilton argued, Congress would have to be empowered by a constitutional amendment.

That episode demonstrates the the constrained nature of Hamilton's way of reading of the Constitution. While committed to the idea of a flexible and vigorous federal government, Hamilton was also committed to the Constitution's function as a limitation on that government's power. When the text of the Constitution indicated that Congress had power, Hamilton urged that that power be used to its utmost. But when the text indicated that Congress did not have a given power, Hamilton insisted that the text be followed, even if he thought the text should be changed in order to facilitate better policy. This approach sets Hamilton clearly within the conservative camp when it comes to interpreting the Constitution -- as in his general approach to law & government, he would be an unorthodox conservative today, but a conservative nonetheless. Constitutional structure & constitutional language both mattered to Hamilton. And it is in both that he found the best guarantees against an overly expansive sweep of government power.

(Tom's post immediately below demonstrates this point as well in reference to the Senate's role in judicial appointments.)

Monday, February 08, 2016

A Hamiltonian defense of returning power to the States

Walter Russell Mead provides an argument for such over at The American Interest. As somebody who is more sympathetic with Hamiltonianism as opposed to Jeffersonianism, I heartily concur with the article's points. First, for the Hamiltonian there is an embrace of realism about the need for a strong and active federal government. Instead of adhering to a rigid ideology of decentralization, the Hamiltonian approach is a prudential one, that seeks to apply the wisdom of localism tempered by an acknowledgment of the needs of the nation. As the article linked above puts it:

I have enough Hamiltonianism in my political DNA to believe that the United States needs a strong federal government. Providing for the national defense, managing the country’s international engagements and commitments, supporting economic development through the provision of a sound national currency and the prudent (but not innovation-suppressing) regulation of financial markets, and the regulation of interstate commerce are all big assignments and they cannot be fulfilled without a strong national state. In addition, the federal government has a special historical responsibility to assure African-Americans equal treatment under the law. This responsibility, given to the federal government by the Civil War-era amendments to the Constitution and renewed by the Civil Rights movement, requires the federal government to monitor a range of practices in the private sector and in state and local governments across the land. In a perfect world, the federal government would not need these powers, but with almost 400 years of history behind us on this issue, federal action remains necessary as we struggle to defeat the lingering after-effects of the great national curse of race prejudice.But that strong, active federal government doesn't, in a Hamiltonian world, mean that the federal government should be omnipresent or have delusions of omnicompetence:

Even so, I believe that the time has come when we urgently need to move power and policy from the federal level back to the states and localities — not to weaken or undermine the strong federal government that we need, but to improve and defend it. Vermont and Utah are very different places with very different ideas about social, educational and economic policy. They have different needs and different priorities. Only rarely can the federal government make the people in both states happy; more usually, the compromises built into federal policy and programs will irritate the residents of both states. Left to themselves, the people in Utah and Vermont would develop very different policies on matters ranging from drug use to abortion to gay rights to education. Within some very broad limits (and with special attention to race given its special constitutional status) I don’t see why, they shouldn’t be free to do so.Hamilton generally gets a bad rap when it comes to questions of the proper scope of government power. Many libertarians, and not a few conservatives, tend to view Hamilton as an early example of a modern liberal -- somebody who thought that federal power should be essentially unlimited. A fair and balanced reading of Hamilton's writings and his career would indicate that such a view of Hamilton is mistaken. While Hamilton believed in an energetic and active federal government, he believed that such a government should be limited in its powers and scope. Not hobbled to the point of impotence, but not omnipotent over the States and local communities either. It's a vision that is worth exploring and not dismissing, particularly as our nation grapples with problems that call not for universal solutions but ones that are local and regional in character.

Saturday, January 23, 2016

The Intellectual Origins of Jeffersonian Democracy

Oftentimes influential books are relatively short. Thomas Paine's Common Sense, for example, was originally published as a pamphlet. The Communist Manifesto, one of the most perniciously influential books of the last 200 years, is short as well. So, when it comes to influence, the massive treatise isn't always the one that people turn to. In an academic culture that often values heft over insight, one book that demonstrates that less can be more is the late Douglass Adair's 185 page landmark study, The Roots of Jeffersonian Democracy. Written in 1943, the work was Adair's doctoral dissertation at Yale. It is now back in print, republished in 2000 by Lexington Books.

As the introduction to the Lexington Books edition puts it, the checkout list for Adair's dissertation reads like "a who's who of early American history." The number of scholars across ideological and methodological camps who have been influenced by Adair is astounding. And there is good reason that Adair's dissertation is so influential: it is that rarity among books that start as dissertations -- a clear, concisely worded, focused study of its topic. And Adair's topic is ambitious, no less than understanding the roots of the political theories of the formative period of the American Republic.

While the title of Adair's dissertation centers on Jeffersonianism, most of the study is devoted not to Jefferson but to those around him. Madison figures prominently, but so does Hamilton. Adair's presentation of Hamilton is generous, and Adair goes out of his way to discuss Hamilton's contributions to the emerging constitutionalism of the early American nation. And not just Hamilton's influence on the constitutional convention and the ratifying debates afterward, but Hamilton's deeper political convictions regarding the need for a "balanced government," one that was limited not only in scope but also in its ability to concentrate power in the hands of any one group, interest or person.

Part of this idea of balance included the notion of an aristocracy of ability and position that would be able to temper the passions of the mass of the people. It was this emphasis on balanced government that, in Adair's view, motivated the Federalist Party, and bound together such different personalities as Hamilton and John Adams in common political endeavor.

Adair's study also details the powerful influence that classical Greco-Roman political theory had on the discussions regarding American government during the founding period. Aristotle and his disciples as well as Plato's student Xenophon figured prominently not only in Federalist political theory, but in the rising political ideology of the Jeffersonian Republicans. Adair notes that Hamilton's concerns for balanced government were bolstered by appeals to classical theorists. In Adair's telling, Hamiliton was widely although not deeply read in the classics, and he was so enamored of classical political theory that he "could not turn his reading of ancient history at all toward the clarification and ordering of the American world in which he lived." Indeed, Adair's study of this component of Hamilton's intellectual formation serves as a cautionary tale about the risks of imbibing too much of the classics at the expense of understanding one's present surroundings. As Adair puts it, "his [Hamilton's] classical learning operated to distort and becloud so many political phenomena lying under his very eyes that he could never deal with them realistically, except in minor matters of technique."

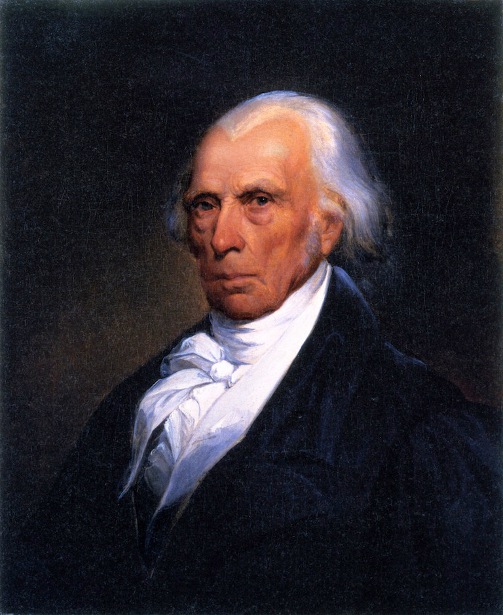

The real star of Adair's book is James Madison, the one-time disciple of Washington and ally of Hamilton who eventually became the scholar- and politician-apprentice to Thomas Jefferson. Madison, in Adair's view, had a far more nuanced and realistic understanding of both of classical patrimony and the political reality of the early American Republic. Madison's understanding of the necessary constitutional order included limitations on both federal and state power, a recognition of the rights of the majority along with a commitment to the protection of the rights of the minority. According to Adair, Madison's defense of the Virginia Plan in the constitutional convention flowed out of these concerns, and reflected a prudential approach to ensuring both minority rights and majority governance. In line with Republican political ideas, Madison did not see history, as Adair puts it, "just the struggle of the rich and the poor trying to devour each other. The problem of faction did not pivot entirely upon the conflict of haves and have-nots." With this insight, Madison escaped the trap of classical political theory, eluding the chains of the Greek and Roman philosophers who saw such struggle at the heart of every system of government. And for this escape Madison was indebted in no small part to writers of the Scottish Enlightenment, notably David Hume, as Adair details.

This isn't to say that Madison and the Jeffersonian Republicans were able to maintain a completely clear-headed view of early American politics. If Hamilton and the Federalists got lost in classical political theory, Madison and the other Jeffersonians fell into the myth of the "virtuous farmer." The "ideal commonwealth," as Adair summarizes Madison's views, "would operate among a nation of husbandmen[.]" And it is in this regard that Adair's study loses much of its energy. Adair fails to see that just as the Federalists were too committed to classical political theory, the Jeffersonians were too committed to an agrarian polity that was rapidly losing ground to the rising industrial economy of the West. Adair didn't see that it was precisely in this way that the Jeffersonians made a critical misstep, completely overlooking the economic trends that were then a-building. One of the things that is so fascinating about early American Republic is that both the Federalists and the Republicans had such critical and (in hindsight) obvious conceptual errors.

If the Federalists were lost in Greek philosophy, they were at least clear-headed when it came to understanding the way the winds were blowing when it came to economics. If the Jeffersonian Republicans were able to see their immediate political world with clear vision, their agrarian dogmatism left them vulnerable to being blindsided by the emerging world of banks, trade and industrial production. This weakness on the part of the Jeffersonians explains, at least in part, the inability of the Jeffersonian Republicans to dismantle much of the Federalist architecture of government and the economy after the revolutionary election of 1800. Adair did not address this aspect of the respective weaknesses and strengths of the Federalists and Jeffersonians, nor did Adair extend his study to deal with Jefferson's tenure as president. No study, of course, is perfect, but the lack of such discussion is a noted lack in a book that otherwise excels in a deep reading of the intellectual trends of the early republic.

Such a discussion would have provided a better glimpse at something that Adair did note well, namely the pessimism that Jefferson and Madison had at the prospects for the American nation. Indeed, the Jeffersonian inability to understand the new economic realities that were then on the rise led both Madison and Jefferson to hold a pronouncedly negative view of the long-term viability of the new republic. Eventually they thought, as Adair points out, that the republic would become too crowded and too corrupt for constitutional government to remain; "commerce and manufactures" would eventually overwhelm the nation. The best that Madison hoped for was "at least a generation" of constitutional government among the American people.

Its flaws aside, though, it is difficult to heap too much praise on this book. Adair's study is a insightful look into what he describes as "the alien intellectual territory" of Jefferson and Madison. It is notable for its depth, for its insight, and for its examination of the sources for much of the political thought of the early republic. It is a book well worth reading.

As the introduction to the Lexington Books edition puts it, the checkout list for Adair's dissertation reads like "a who's who of early American history." The number of scholars across ideological and methodological camps who have been influenced by Adair is astounding. And there is good reason that Adair's dissertation is so influential: it is that rarity among books that start as dissertations -- a clear, concisely worded, focused study of its topic. And Adair's topic is ambitious, no less than understanding the roots of the political theories of the formative period of the American Republic.

While the title of Adair's dissertation centers on Jeffersonianism, most of the study is devoted not to Jefferson but to those around him. Madison figures prominently, but so does Hamilton. Adair's presentation of Hamilton is generous, and Adair goes out of his way to discuss Hamilton's contributions to the emerging constitutionalism of the early American nation. And not just Hamilton's influence on the constitutional convention and the ratifying debates afterward, but Hamilton's deeper political convictions regarding the need for a "balanced government," one that was limited not only in scope but also in its ability to concentrate power in the hands of any one group, interest or person.

Part of this idea of balance included the notion of an aristocracy of ability and position that would be able to temper the passions of the mass of the people. It was this emphasis on balanced government that, in Adair's view, motivated the Federalist Party, and bound together such different personalities as Hamilton and John Adams in common political endeavor.

Adair's study also details the powerful influence that classical Greco-Roman political theory had on the discussions regarding American government during the founding period. Aristotle and his disciples as well as Plato's student Xenophon figured prominently not only in Federalist political theory, but in the rising political ideology of the Jeffersonian Republicans. Adair notes that Hamilton's concerns for balanced government were bolstered by appeals to classical theorists. In Adair's telling, Hamiliton was widely although not deeply read in the classics, and he was so enamored of classical political theory that he "could not turn his reading of ancient history at all toward the clarification and ordering of the American world in which he lived." Indeed, Adair's study of this component of Hamilton's intellectual formation serves as a cautionary tale about the risks of imbibing too much of the classics at the expense of understanding one's present surroundings. As Adair puts it, "his [Hamilton's] classical learning operated to distort and becloud so many political phenomena lying under his very eyes that he could never deal with them realistically, except in minor matters of technique."

The real star of Adair's book is James Madison, the one-time disciple of Washington and ally of Hamilton who eventually became the scholar- and politician-apprentice to Thomas Jefferson. Madison, in Adair's view, had a far more nuanced and realistic understanding of both of classical patrimony and the political reality of the early American Republic. Madison's understanding of the necessary constitutional order included limitations on both federal and state power, a recognition of the rights of the majority along with a commitment to the protection of the rights of the minority. According to Adair, Madison's defense of the Virginia Plan in the constitutional convention flowed out of these concerns, and reflected a prudential approach to ensuring both minority rights and majority governance. In line with Republican political ideas, Madison did not see history, as Adair puts it, "just the struggle of the rich and the poor trying to devour each other. The problem of faction did not pivot entirely upon the conflict of haves and have-nots." With this insight, Madison escaped the trap of classical political theory, eluding the chains of the Greek and Roman philosophers who saw such struggle at the heart of every system of government. And for this escape Madison was indebted in no small part to writers of the Scottish Enlightenment, notably David Hume, as Adair details.

This isn't to say that Madison and the Jeffersonian Republicans were able to maintain a completely clear-headed view of early American politics. If Hamilton and the Federalists got lost in classical political theory, Madison and the other Jeffersonians fell into the myth of the "virtuous farmer." The "ideal commonwealth," as Adair summarizes Madison's views, "would operate among a nation of husbandmen[.]" And it is in this regard that Adair's study loses much of its energy. Adair fails to see that just as the Federalists were too committed to classical political theory, the Jeffersonians were too committed to an agrarian polity that was rapidly losing ground to the rising industrial economy of the West. Adair didn't see that it was precisely in this way that the Jeffersonians made a critical misstep, completely overlooking the economic trends that were then a-building. One of the things that is so fascinating about early American Republic is that both the Federalists and the Republicans had such critical and (in hindsight) obvious conceptual errors.

If the Federalists were lost in Greek philosophy, they were at least clear-headed when it came to understanding the way the winds were blowing when it came to economics. If the Jeffersonian Republicans were able to see their immediate political world with clear vision, their agrarian dogmatism left them vulnerable to being blindsided by the emerging world of banks, trade and industrial production. This weakness on the part of the Jeffersonians explains, at least in part, the inability of the Jeffersonian Republicans to dismantle much of the Federalist architecture of government and the economy after the revolutionary election of 1800. Adair did not address this aspect of the respective weaknesses and strengths of the Federalists and Jeffersonians, nor did Adair extend his study to deal with Jefferson's tenure as president. No study, of course, is perfect, but the lack of such discussion is a noted lack in a book that otherwise excels in a deep reading of the intellectual trends of the early republic.

Such a discussion would have provided a better glimpse at something that Adair did note well, namely the pessimism that Jefferson and Madison had at the prospects for the American nation. Indeed, the Jeffersonian inability to understand the new economic realities that were then on the rise led both Madison and Jefferson to hold a pronouncedly negative view of the long-term viability of the new republic. Eventually they thought, as Adair points out, that the republic would become too crowded and too corrupt for constitutional government to remain; "commerce and manufactures" would eventually overwhelm the nation. The best that Madison hoped for was "at least a generation" of constitutional government among the American people.

Its flaws aside, though, it is difficult to heap too much praise on this book. Adair's study is a insightful look into what he describes as "the alien intellectual territory" of Jefferson and Madison. It is notable for its depth, for its insight, and for its examination of the sources for much of the political thought of the early republic. It is a book well worth reading.

Monday, October 19, 2015

Against a strict construction of constitutional powers

When reading Hamilton on the Constitution, it is a good idea to recall the wise observation of Russell Kirk that original intent does not always = strict construction. On this point, most modern conservatives part ways with both Kirk & Hamilton when it comes to reading our nation's fundamental charter.

[T]he powers contained in a constitution of government, especially those which concern the general administration of the affairs of a country, its finances, trade, defense, etc., ought to be construed liberally in advancement of the public good. This rule does not depend on the particular form of a government, or on the particular demarcation of the boundaries of its powers, but on the nature and object of government itself. The means by which national exigencies are to be provided for, national inconveniences obviated, national prosperity promoted, are of such infinite variety, extent, and complexity, that there must of necessity be great latitude of discretion in the selection and application of those means. Hence, consequently, the necessity and propriety of exercising the authorities intrusted [sic] to a government on principles of liberal construction.- Alexander Hamilton (1755-1804), Opinion as to the Constitutionality of the Bank of the United States, 1791.

Saturday, October 17, 2015

Brazil needed a man like Alexander Hamilton

That's one of the conclusions to be drawn from this blog post by Walter Russell Mead on Brazil's rise as an economic power: Brazil: What Could Go Wrong? As Mead notes, in the 19th century the United States and Brazil had strikingly similar economies. The reason why the United States surged ahead and Brazil stagnated at the time is to be found in the divergent economic policies the two countries pursued. Brazil clung to an obsolete agrarianism while the United States followed a more realistic economic policy, crafted first by Federalist Founding Father Alexander Hamilton and then by Whig leaders like Daniel Webster and Henry Clay:

In the 19th century Brazil, like the United States, was a commodity producer tied to the British market. Britain was the leading investor in both the US and Brazil, and Britain ate up the lion’s share of their exports. But there was a difference: the United States did some things that Brazil did not. We established manufacturing and financial sectors in our economy that could ultimately rival Great Britain in those fields, and we became a producer of new technologies and world-class companies.

19th century Brazil never managed to build those additional dimensions of a strong market economy. In a sense, all of Brazil continued to develop like the American South: a commodity exporting economy based on slavery (not abolished until the 1880s) and peonage. And like the Confederacy, Brazilians long favored a decentralized form of government in which states largely ignored the central government in Rio.

Decentralization spared Brazil some of the bitter social conflicts that shook countries like Mexico and Argentina in the first century of independence, but there was nobody like Alexander Hamilton, Henry Clay and Daniel Webster with the power and the will to turn Brazil into a cutting edge economic power.Read it all. It cannot be emphasized enought that the prosperity of the United States is built not on an agrarian Jeffersonian vision -- the kind of economic policy that lead Brazil into over a century of economic malaise -- but on the vision of men like Alexander Hamilton.

Wednesday, September 30, 2015

Madison's Hamiltonian interpretation of the Constitution

In light of Tom's post last Friday quoting Madison on constitutional interpretation, I thought I would pass along a link to this this book review posted over at The American Conservative: What Madison Meant. Author Ralph Ketcham notes that Madison in his later years drew increasingly close to the Hamiltonian judicial theories of the great Federalist chief justice of the Supreme Court, John Marshall. The review is well worth a read, to help counter some of the more recent Jeffersonian fixation on the Right regarding the best approach to take regarding constitutional interpretation.

As Russell Kirk wrote in his book on the American Constitution, Rights and Duties, an originalist approach to the Constitution is not necessarily an approach that requires strict construction. Hamilton certainly would have agreed with that, as would have Marshall & his ally on the bench, Joseph Story, Madison's greatest appointment to the judiciary. And, as Ketcham's review demonstrates, Madison would have agreed to that sentiment as well. For those familiar with Madison and the arc of his views on government, it is little surprise that in his later years he moved away from Jefferson's views of the Constitution & back towards his original insights, hammered out with his past friend Alexander Hamilton.

Madison's shift towards a more Hamiltonian approach to the Constitution needs to be balanced with his long-term commitment to the diversity of local communities and the liberties of individual citizens. One of the key building blocks of American order has been the pluralism that has existed within our country since the colonial period. It was precisely the coalescing of the various colonies into a single American nation that solidified that pluralism, as no single colony had sufficient weight to dominate the entirety of the country. Thus New England remained separate from the South, Pennsylvania from Virginia, South Carolina from its neighbors in Georgia and North Carolina. The fragmented cultures, demographics and economies of the various colonies, later states, prevented the country from taking on one particular characteristic.

As a consequence, there were a variety of religious, economic, political & social interests throughout America at the time of the Founding, and it was this diversity that spurred on the growth of liberty. Since no single state, demographic group, religion or economic interest could control the whole, it was in the interest of each differing segment of the country to support freedom. Madison embraced this pluralism through his public career, often in opposition to Hamilton and the policies that brilliant if flawed statesman favored. At the same time, Madison's commitment to political & regional diversity was deployed to defend a vibrant & strong general government in his greatest collaborative work with Hamilton, The Federalist Papers.

This point was emphasized brilliantly by James Madison in one of his most notable contributions to The Federalist, Essay # 51, dated February 6, 1788, where Madison wrote to console fears that the proposed Constitution would stamp down religious & political rights through the creation of a federal leviathan. Madison emphasized that the true foundation of liberty in the United States came not from paper guarantees but from the vibrant & varied interests within the country, interests that emphasize not the centralization of power but rather the pursuit of the common good through federalism. As Madison put it so well:

It would not be a stretch to say that Madison's turn toward Hamiltonian principles was in many ways a return to his own.

As Russell Kirk wrote in his book on the American Constitution, Rights and Duties, an originalist approach to the Constitution is not necessarily an approach that requires strict construction. Hamilton certainly would have agreed with that, as would have Marshall & his ally on the bench, Joseph Story, Madison's greatest appointment to the judiciary. And, as Ketcham's review demonstrates, Madison would have agreed to that sentiment as well. For those familiar with Madison and the arc of his views on government, it is little surprise that in his later years he moved away from Jefferson's views of the Constitution & back towards his original insights, hammered out with his past friend Alexander Hamilton.

Madison's shift towards a more Hamiltonian approach to the Constitution needs to be balanced with his long-term commitment to the diversity of local communities and the liberties of individual citizens. One of the key building blocks of American order has been the pluralism that has existed within our country since the colonial period. It was precisely the coalescing of the various colonies into a single American nation that solidified that pluralism, as no single colony had sufficient weight to dominate the entirety of the country. Thus New England remained separate from the South, Pennsylvania from Virginia, South Carolina from its neighbors in Georgia and North Carolina. The fragmented cultures, demographics and economies of the various colonies, later states, prevented the country from taking on one particular characteristic.

As a consequence, there were a variety of religious, economic, political & social interests throughout America at the time of the Founding, and it was this diversity that spurred on the growth of liberty. Since no single state, demographic group, religion or economic interest could control the whole, it was in the interest of each differing segment of the country to support freedom. Madison embraced this pluralism through his public career, often in opposition to Hamilton and the policies that brilliant if flawed statesman favored. At the same time, Madison's commitment to political & regional diversity was deployed to defend a vibrant & strong general government in his greatest collaborative work with Hamilton, The Federalist Papers.

This point was emphasized brilliantly by James Madison in one of his most notable contributions to The Federalist, Essay # 51, dated February 6, 1788, where Madison wrote to console fears that the proposed Constitution would stamp down religious & political rights through the creation of a federal leviathan. Madison emphasized that the true foundation of liberty in the United States came not from paper guarantees but from the vibrant & varied interests within the country, interests that emphasize not the centralization of power but rather the pursuit of the common good through federalism. As Madison put it so well:

In a free government the security for civil rights must be the same as that for religious rights. It consists in the one case in the multiplicity of interests, and in the other in the multiplicity of sects. The degree of security in both cases will depend on the number of interests and sects; and this may be presumed to depend on the extent of country and number of people comprehended under the same government. This view of the subject must particularly recommend a proper federal system to all the sincere and considerate friends of republican government, since it shows that in exact proportion as the territory of the Union may be formed into more circumscribed Confederacies, or States oppressive combinations of a majority will be facilitated: the best security, under the republican forms, for the rights of every class of citizens, will be diminished: and consequently the stability and independence of some member of the government, the only other security, must be proportionately increased. Justice is the end of government. It is the end of civil society. It ever has been and ever will be pursued until it be obtained, or until liberty be lost in the pursuit. In a society under the forms of which the stronger faction can readily unite and oppress the weaker, anarchy may as truly be said to reign as in a state of nature, where the weaker individual is not secured against the violence of the stronger; and as, in the latter state, even the stronger individuals are prompted, by the uncertainty of their condition, to submit to a government which may protect the weak as well as themselves; so, in the former state, will the more powerful factions or parties be gradually induced, by a like motive, to wish for a government which will protect all parties, the weaker as well as the more powerful. It can be little doubted that if the State of Rhode Island was separated from the Confederacy and left to itself, the insecurity of rights under the popular form of government within such narrow limits would be displayed by such reiterated oppressions of factious majorities that some power altogether independent of the people would soon be called for by the voice of the very factions whose misrule had proved the necessity of it. In the extended republic of the United States, and among the great variety of interests, parties, and sects which it embraces, a coalition of a majority of the whole society could seldom take place on any other principles than those of justice and the general good; whilst there being thus less danger to a minor from the will of a major party, there must be less pretext, also, to provide for the security of the former, by introducing into the government a will not dependent on the latter, or, in other words, a will independent of the society itself. It is no less certain than it is important, notwithstanding the contrary opinions which have been entertained, that the larger the society, provided it lie within a practical sphere, the more duly capable it will be of self-government. And happily for the republican cause, the practicable sphere may be carried to a very great extent, by a judicious modification and mixture of the federal principle.Federalism, in Madison's presentation, thus forms perhaps the principal guarantee of liberty in the American Republic. Such federalism means a balanced government, with proper powers vested in a general government as well as proper powers retained by the states to deal with properly local issues. Madison was no radical. His defense of "the federal principle," the idea of both a strong general government & robust local governments, was then & remains today an almost perfect expression of that unique American ideal of the pluralism of interest guaranteeing liberty within the construct of a constitutional order that was itself divided between general & particular structures, between national & state governments.

It would not be a stretch to say that Madison's turn toward Hamiltonian principles was in many ways a return to his own.

Friday, July 17, 2015

Where do our rights come from?

The op-ed is from a while ago (2012), but here's Lawrence Lindsey over at the Wall Street Journal reflecting on the question in this blog post's title: Geithner and the "Privilege" of Being American. As Lindsey points out, the Founding Fathers thought that our fundamental rights of life and liberty precede the State. In other words, the State does not provide us with our rights and grant them to us, rather the State merely recognizes rights that already exist. Our rights are not boons provided to us by our betters, by those who rule over us. The task of our leaders is to protect the rights that are ours by nature.

Of course, rights and duties need effective expression though the positive law. As the late Russell Kirk never tired of pointing out, natural law and natural justice are not substitutes for positive law, but rather the predicates upon which positive law depends to function properly to order human community towards order, justice and peace.

The weak spot in Lindsey's argument is that he fails to identify precisely where our rights do come from. If not from the State, then what is their basis? For the Founders, the source of our rights is divine Providence, in the God who creates and sustains the world -- "nature's God" to use a phrase from the Declaration of Independence. At the root of liberty, at the root of limited government, at the root of human freedom, is the truth that prior to and above the State there exists a Power to whom the State itself is subordinate. Take away that truth and the foundation for human rights & limited government collapses in a heap.

Alexander Hamilton, that great American founder whose memory as of late has been under continued assault, understood this well. Writing in The Farmer Refuted in 1775, Hamilton built upon the work of the English jurist William Blackstone to eloquently hold forth on the origin of human rights:

"And yet the same revolutionary beliefs for which our forebears fought are still at issue around the globe -- the belief that the rights of man come not from the generosity of the state, but from the hand of God." Amen to that, Mr. President. Amen to that.

Of course, rights and duties need effective expression though the positive law. As the late Russell Kirk never tired of pointing out, natural law and natural justice are not substitutes for positive law, but rather the predicates upon which positive law depends to function properly to order human community towards order, justice and peace.

The weak spot in Lindsey's argument is that he fails to identify precisely where our rights do come from. If not from the State, then what is their basis? For the Founders, the source of our rights is divine Providence, in the God who creates and sustains the world -- "nature's God" to use a phrase from the Declaration of Independence. At the root of liberty, at the root of limited government, at the root of human freedom, is the truth that prior to and above the State there exists a Power to whom the State itself is subordinate. Take away that truth and the foundation for human rights & limited government collapses in a heap.

Alexander Hamilton, that great American founder whose memory as of late has been under continued assault, understood this well. Writing in The Farmer Refuted in 1775, Hamilton built upon the work of the English jurist William Blackstone to eloquently hold forth on the origin of human rights:

Good and wise men, in all ages, have embraced a very dissimilar theory. They have supposed, that the deity, from the relations, we stand in, to himself and to each other, has constituted an eternal and immutable law, which is, indispensibly, obligatory upon all mankind, prior to any human institution whatever.

This is what is called the law of nature, "which, being coeval with mankind, and dictated by God himself, is, of course, superior in obligation to any other. It is binding over all the globe, in all countries, and at all times. No human laws are of any validity, if contrary to this; and such of them as are valid, derive all their authority, mediately, or immediately, from this original."

Upon this law, depend the natural rights of mankind, the supreme being gave existence to man, together with the means of preserving and beatifying that existence. He endowed him with rational faculties, by the help of which, to discern and pursue such things, as were consistent with his duty and interest, and invested him with an inviolable right to personal liberty, and personal safety.And then in words that stand among the most powerful written during the American revolutionary period, Hamilton thundered:

The sacred rights of mankind are not to be rummaged for, among old parchments, or musty records. They are written, as with a sun beam, in the whole volume of human nature, by the hand of the divinity itself; and can never be erased or obscured by mortal power.The relationship between natural law and human rights has been a well-understood and affirmed part of American law and politics for most of our history, until fairly recent times. Not restricted to the Right, liberals long affirmed this fundamental principle, both in theory and in political rhetoric at the highest levels, as this except from President John F. Kennedy's Inaugural Address shows:

"And yet the same revolutionary beliefs for which our forebears fought are still at issue around the globe -- the belief that the rights of man come not from the generosity of the state, but from the hand of God." Amen to that, Mr. President. Amen to that.

Tuesday, June 30, 2015

"The greatest security in a Republic"

Alexander Hamilton on the best defense of the American system of government, namely respect for the laws that govern us:

- Alexander Hamilton (1755-1804), Tully No. III, Aug. 28, 1794, reprinted in Alexander Hamilton: Writings (Library of America: 2001), pg. 830.If it were to be asked, What is the most sacred duty and the greatest security in a Republic? the answer would be, An inviolable respect for the Constitution and Laws -- the first growing out of the last. It is by this, in a great degree, that the rich and powerful are to be restrained from enterprises against the common liberty -- operated upon by the influence of a general sentiment, by their interest in the principle, and by the obstacles which the habit it produces erects against innovation and encroachment. It is by this, in a still greater degree, that caballers, intriguers, and demagogues are prevented from climbing on the shoulders of faction to the tempting seats of usurpation and tyranny.

Of course, it helps if those laws are themselves respectable.

Labels:

Alexander Hamilton,

American Founding,

rule of law

Monday, March 23, 2015

Ordered liberty & the political rhetoric of Alexander Hamilton

A lengthy essay on that topic by one of the master historians of the American founding may be found here: The Rhetoric of Alexander Hamilton. The author, Forest McDonald, does a very good job dispatching some of the gross distortions of Hamilton that have persisted since the radical Jeffersonians took it upon themselves to poison the record regarding this most uniquely American founding father. Far from seeking to create a centralized government based on greed and corruption, Hamilton sought to ensure that balanced government would be motivated by virtue, natural law and the principle of proper and precise debate over public policy issues.

While Jeffersonians were perfecting bare knuckle politics, Hamilton sought to elevate discourse and speak clearly on the pressing issues of the day. As McDonald notes, Hamilton was unsure that the American experiment in constitutional government would succeed, but he was adamant in his commitment to fight for its viability in a world growing increasingly swamped by the fervor of ideology. And the key to viability was (& is) to shift the discussion from rights to duties, from benefits to obligations:

While Jeffersonians were perfecting bare knuckle politics, Hamilton sought to elevate discourse and speak clearly on the pressing issues of the day. As McDonald notes, Hamilton was unsure that the American experiment in constitutional government would succeed, but he was adamant in his commitment to fight for its viability in a world growing increasingly swamped by the fervor of ideology. And the key to viability was (& is) to shift the discussion from rights to duties, from benefits to obligations:

More than most of his countrymen, he doubted that the experiment could succeed; more than any of them, he was dedicated to making the effort. He perceived clearly that political rhetoric of the highest order was necessary to the attempt, for such is essential to statecraft in a republic. Now, we hear a great deal these days about the public’s “right to know.” That is a perversion of the truth, even as modern public relations, propaganda, and political blather are perversions of classical rhetoric. If the republic is to survive, the emphasis must be shifted from rights back to obligations. It is the obligation, not the right, of the citizen of a republic to be informed; it is the obligation of the public servant to inform him and simultaneously to raise his standards of judgment. In adapting his style to his audience, Hamilton was fulfilling his part of the obligation.Ordered liberty was the goal of Hamilton's work. And ordered liberty requires not just a right ordering of the affairs of government, it requires a citizenry oriented to both freedom & civic virtue. McDonald's essay does a fantastic job of showing Hamilton's commitment to defending ordered liberty against its enemies, using clear, energetic language grounded in the belief in morality, duty & prudential principle.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)