"Moreover, man, who was created for freedom, bears within himself the wound of original sin, which constantly draws him towards evil and puts him in need of redemption. Not only is this doctrine an integral part of Christian revelation; it also has great hermeneutical value insofar as it helps one to understand human reality. Man tends towards good, but he is also capable of evil. He can transcend his immediate interest and still remain bound to it. The social order will be all the more stable, the more it takes this fact into account and does not place in opposition personal interest and the interests of society as a whole, but rather seeks ways to bring them into fruitful harmony. In fact, where self-interest is violently suppressed, it is replaced by a burdensome system of bureaucratic control which dries up the wellsprings of initiative and creativity. When people think they possess the secret of a perfect social organization which makes evil impossible, they also think that they can use any means, including violence and deceit, in order to bring that organization into being. Politics then becomes a "secular religion" which operates under the illusion of creating paradise in this world. But no political society — which possesses its own autonomy and laws55 — can ever be confused with the Kingdom of God. The Gospel parable of the weeds among the wheat (cf. Mt 13:24-30; 36-43) teaches that it is for God alone to separate the subjects of the Kingdom from the subjects of the Evil One, and that this judgment will take place at the end of time. By presuming to anticipate judgment here and now, man puts himself in the place of God and sets himself against the patience of God."

-- Centesimus Annus (May 1, 1991).

Tradition is not the worship of ashes, but the preservation of fire.—Gustav Mahler

Showing posts with label Religion and politics. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Religion and politics. Show all posts

Friday, May 26, 2017

Wednesday, May 24, 2017

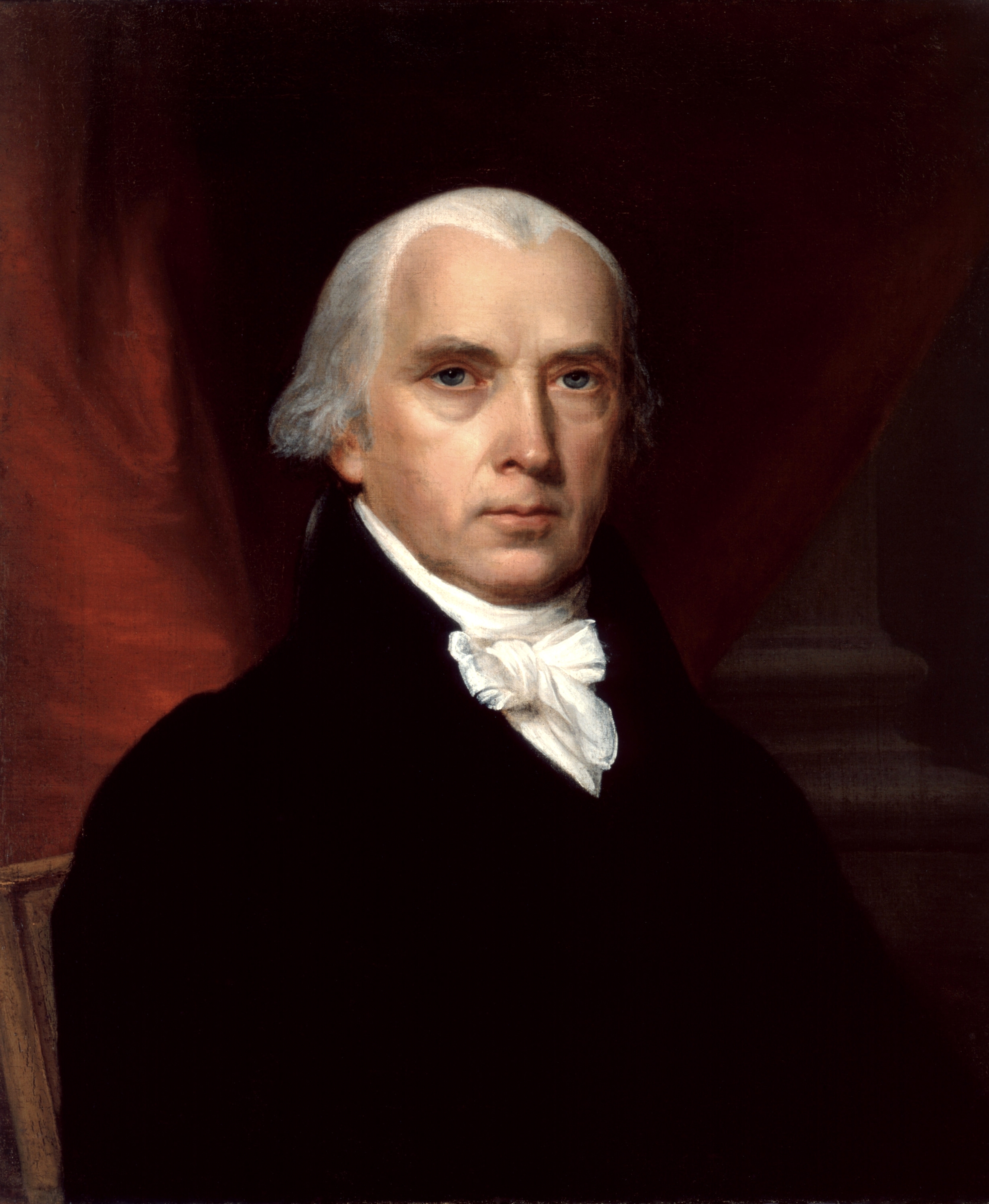

James Madison on church-state separation

"It may not be easy, in every possible case, to trace the line of separation between the rights of religion and the Civil authority with such distinctness as to avoid collisions and doubts on unessential points. The tendency to usurpation on one side or the other, or to a corrupting coalition or alliance between them, will be best guarded agst. by an entire abstinence of the Govt. from interference in any way whatsoever, beyond the necessity of preserving public order, and protecting each sect agst. trespasses on its legal rights by others."-- Letter to the Reverend Jasper Adams, January 1, 1832.

Sunday, September 11, 2016

What Washington knew about the link between property rights and religious liberty

One of the treasures of American literature are George Washington's letters to various groups of citizens following his election as the first president of the United States under our current Constitution. The letters are short and contain concise and dense reflections on the nature of ordered liberty in the new American Republic, explaining the nature and scope of freedom under the Constitution.

Of particular interest is Washington's letter to the Jewish community in Newport, Rhode Island. Washington wrote the letter on August 21, 1790, as a response to a statement of welcome delivered by one of the leaders of the Touro Synagogue in Newport on the occasion of Washington's visit to that town following the ratification of the Constitution by Rhode Island. In the letter, Washington expresses his conviction about the importance of property rights to protecting other rights under the Constitution:

Of particular interest is Washington's letter to the Jewish community in Newport, Rhode Island. Washington wrote the letter on August 21, 1790, as a response to a statement of welcome delivered by one of the leaders of the Touro Synagogue in Newport on the occasion of Washington's visit to that town following the ratification of the Constitution by Rhode Island. In the letter, Washington expresses his conviction about the importance of property rights to protecting other rights under the Constitution:

Gentlemen:

While I received with much satisfaction your address replete with expressions of esteem, I rejoice in the opportunity of assuring you that I shall always retain grateful remembrance of the cordial welcome I experienced on my visit to Newport from all classes of citizens.

The reflection on the days of difficulty and danger which are past is rendered the more sweet from a consciousness that they are succeeded by days of uncommon prosperity and security.

If we have wisdom to make the best use of the advantages with which we are now favored, we cannot fail, under the just administration of a good government, to become a great and happy people.

The citizens of the United States of America have a right to applaud themselves for having given to mankind examples of an enlarged and liberal policy—a policy worthy of imitation. All possess alike liberty of conscience and immunities of citizenship.

It is now no more that toleration is spoken of as if it were the indulgence of one class of people that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights, for, happily, the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens in giving it on all occasions their effectual support.

It would be inconsistent with the frankness of my character not to avow that I am pleased with your favorable opinion of my administration and fervent wishes for my felicity.

May the children of the stock of Abraham who dwell in this land continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other inhabitants—while every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and fig tree and there shall be none to make him afraid.

May the father of all mercies scatter light, and not darkness, upon our paths, and make us all in our several vocations useful here, and in His own due time and way everlastingly happy.

G. Washington

This is a telling statement about the nature of religious liberty, recognized by the Constitution, grounded not in the preference of the elite but in natural rights common to all and the duties of citizenship. Of additional interest is the linking of religious liberty and property rights. To draw that linkage in his letter Washington quotes the Prophet Micah from the Hebrew Bible:

And every man shall sit under his vine, and under his fig tree, and there shall be none to make them afraid: for the mouth of the Lord of hosts hath spoken. (Micah 4:4, Douay-Rheims Version.)

Property rights serve as an essential bulwark for other freedoms, in the they provide citizens with the space and the means to exercise their other rights. Without property rights, there can be no liberty of speech, of religion, of the press, or to be secure against unlawful searches and seizures. Washington understood this and propounded a constitutional order where citizens -- not just those favored by the government -- may sit secure in their possessions, "and there shall be done to make them afraid." To be secure in your property is to be free indeed.

Sunday, April 03, 2016

Does it matter if any of the American founders were Christians?

Some time ago, I used to post over at the American Creation blog, and one of the major recurring topics over there regards the religious beliefs & practice of the American founders. Were they Christians? What kind of Christians? Devout? Lax? Nicene orthodox? Unitarian? You get the idea.

Apart from the very real difficulty of accurately describing the religious views of some of the founders (who, for example, can coherently describe whatever Thomas Jefferson happened to believe at any given moment?), this kind of questioning is quite popular. It shows up quite a bit in constitutional law scholarship discussing the First Amendment's religion clauses and the role of faith in public life. And yet...

Over at The American Conservative online, writer Paul Gottfried argues that this whole line of questioning is mistaken: Was George Washington a Christian? According to Gottfried's approach the relevant question isn't what did the founders believe? rather it is what kind of social and political order did the founders intend to create? Gottfried has some thoughts on both questions, and his ideas are well worth pondering. I particularly am struck by his framing of the debate about religion and the Founding Era. Worth a read.

Apart from the very real difficulty of accurately describing the religious views of some of the founders (who, for example, can coherently describe whatever Thomas Jefferson happened to believe at any given moment?), this kind of questioning is quite popular. It shows up quite a bit in constitutional law scholarship discussing the First Amendment's religion clauses and the role of faith in public life. And yet...

Over at The American Conservative online, writer Paul Gottfried argues that this whole line of questioning is mistaken: Was George Washington a Christian? According to Gottfried's approach the relevant question isn't what did the founders believe? rather it is what kind of social and political order did the founders intend to create? Gottfried has some thoughts on both questions, and his ideas are well worth pondering. I particularly am struck by his framing of the debate about religion and the Founding Era. Worth a read.

Wednesday, October 21, 2015

Gordon Wood on Freemasonry and the American founding

When it first hit print, I slowly worked my way through Gordon Wood's massive book on the post-revolutionary period in American history, Empire of Liberty (Oxford Univ. Press, 2009). The book demands slow reading -- each page is packed with detail and interpretation, and it is simply a joy to mull over Wood's insights. The book is a tome -- 738 pages excluding the biblographic essay -- but almost every page is a winner. Wood has put together a landmark book here, one that builds off of and massively expands upon his earlier work in Radicalism of the American Revolution. There was been quite a bit of some back and forth within the historical profession on the role that Freemasonry played in the American Founding. Wood addresses the question in the first part of his book, proposing that Masonry played a dual role as a source of unity in America and as a new religion designed to replace Christianity for those skeptical of Christianity's claims. His take on Masonry is set out on page 51 of the book:

Freemasonry was a surrogate religion for enlightened men suspicious of traditional Christianity. It offered ritual, mystery, and communality without the enthusiasm and sectarian bigotry of organized religion. But Masonry was not only an enlightened institution; with the Revolution, it became a republican one as well. As George Washington said, it was "a lodge for the virtues." As Masonic lodges had always been places where men who differed in everyday affairs -- politically, socially, even religiously -- could "all meet amicably, and converse sociably together." There in the lodges, the Masons told themselves, "we discover no estrangement of behavior, nor alienation of affection." Masonry had alway sought unity and harmony in a society increasingly diverse and fragmented. It traditionally had prided itself on being, as one Mason put it, "the Center of Union and the means of conciliating friendship among men that might otherwise have remained at perpetual distance."As Wood makes clear, Masonry served a religious as well as a civic function. Its importance in the Founding Period was not simply social or political. It stood alongside Christianity as a source of religious values and perspective for many of the Founders.

Labels:

American Founding,

Freemasons,

Religion and politics

Sunday, October 11, 2015

Jack Kennedy didn't run on his Catholic faith, but away from it

CHUCK TODD: Should a president's faith matter? Should your faith matter to voters?

DR. BEN CARSON: Well, I guess it depends on what that faith is. If it's inconsistent with the values and principles of America, then of course it should matter. But if it fits within the realm of America and consistent with the Constitution, no problem.

CHUCK TODD: So do you believe that Islam is consistent with the Constitution?

DR. BEN CARSON: No, I don't, I do not.

CHUCK TODD: So you--

DR. BEN CARSON: I would not advocate that we put a Muslim in charge of this nation. I absolutely would not agree with that.

Well, of course that depends on what we mean by

"Muslim," just as in 1960 when Jack Kennedy was running, what we mean

by "Catholic." In a famous face-down with 400 years of the great

American tradition of anti-Catholicism, and now face-to-face with some 300

skeptical Protestant preachers, Kennedy affirmed he wouldn't let his church get

in the way of the American state, and on that level, the literal separation of

church and state is hardly controversial.

Which brings us to Denver [now Philadelphia] Archbishop Charles J. Chaput's 2010 remarks on JFK's electoral tactic some 50 years

before:

After offering caveats about his remarks, Archbishop Chaput emphasized the need for ecumenism and dialogue based on truth as opposed to superficial niceties. He then remarked, “We also urgently owe each other solidarity and support in dealing with a culture that increasingly derides religious faith in general and the Christian faith in particular.”

During his talk, the archbishop noted that there are currently “more Catholics in national public office” than there ever have been in American history.

“But,” he continued, “I wonder if we’ve ever had fewer of them who can coherently explain how their faith informs their work, or who even feel obligated to try. The life of our country is no more 'Catholic' or 'Christian' than it was 100 years ago. In fact it's arguably less so.”

One of the reasons why this problem exists, he explained, is that too many Christian individuals, Protestant and Catholic alike, live their faith as if it were “private idiosyncrasy” which they try to prevent from becoming a “public nuisance.”

Recounting the historical context that led to the current state of affairs, Archbishop Chaput referred to a speech that the late John F. Kennedy made while running for president in 1960 which greatly affected the modern relationship between religion and American politics. At his speech almost fifty years ago, President Kennedy had the arduous task of convincing 300 uneasy Protestant ministers in a Houston address that his Catholic faith would not impede his ability to lead the country. Successful in his attempt, “Kennedy convinced the country, if not the ministers, and went on to be elected,” he recalled.

“And his speech left a lasting mark on American politics,” the prelate added.

“And he wasn’t merely 'wrong,'” the archbishop continued. “His Houston remarks profoundly undermined the place not just of Catholics, but of all religious believers, in America’s public life and political conversation. Today, half a century later, we’re paying for the damage.”

“To his credit,” he noted, “Kennedy said that if his duties as President should 'ever require me to violate my conscience or violate the national interest, I would resign the office.' He also warned that he would not 'disavow my views or my church in order to win this election.'”

“But in its effect, the Houston speech did exactly that. It began the project of walling religion away from the process of governance in a new and aggressive way. It also divided a person’s private beliefs from his or her public duties. And it set 'the national interest' over and against 'outside religious pressures or dictates.'”

Archbishop Chaput then clarified that although “John Kennedy didn’t create the trends in American life that I’ve described,” his speech “clearly fed them.”

So yes, in this enlightened 21st century, any Muslim whose

character and actions are indistinguishable from any non-Muslim's should be no

less acceptable or rejectable than any other random fellow off the street. But perhaps because since Ben Carson

apparently takes his faith and religion seriously, he was extending the same

consideration to our Muslim-in-theory here.

As Archbishop Chaput noted, there are currently “more

Catholics in national public office” than there ever have been in American

history. American Catholics established a century-long record of

trustworthiness and fidelity to the Constitution. We have barely a handful of

Muslims in public office now, and I'd imagine fewer than 100 in all of American

history on any level, national, state or even local.

I admire the Jehovah's Witnesses, who live their faith in a

way that few other American Christians do. The JW's were at the forefront of groundbreaking constitutional litigation in the 1930s and 40s, and

"mainstream" Christians today owe a lot to them on the religious

freedom front.

Like the Amish, though, JW's don't really run for office, so

it's hard to tell what would happen if you turned your city council over to

their control. So too, if the subject group were JW's or Amish or

Scientologists or young-earth creationists or New Agers or whathaveyous, it's

highly questionable whether Ben Carson's attackers would blithely pull the

lever without a serious JFK-style shakedown.

That's all Ben Carson was trying to say, I reckon, and had

it been an actual discussion and not a pseudo-journalistic ambush by NBC's

Chuck Todd [which hey, it's Todd's job], Carson might have been able to make

that clear.

Jack Kennedy didn't run on his Catholic faith, but away from

it. If an American Muslim wants to copy Jack's act, well, ironically he's

probably not going to get Ben Carson's vote that way either.

Labels:

Catholicism,

God and religion,

JFK,

Religion and politics

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)