A decision theorist was struggling whether to accept an offer from a rival university or to stay. His colleague took him aside and said, “Just maximize your expected utility – you always write about doing this.” Exasperated, the decision theorist responded, “Come on, this is serious.”

The joke works because, unlike the hard sciences, the social sciences have served up too little nourishment to satisfy a critical mind. Years ago, a researcher proved – using commonly-accepted practices – that eating chocolate makes you lose weight. The social and pop scientists can prove anything if they are only ever required to produce a theory, rather than actual results.

Theirs is the legacy of the magicians, who proved not by results or common sense, but by fantastic-sounding theories. This was the fount of Twain's humor in A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court where, in but one comical example, the yankee set out to investigate what evil spell had been cast on the town's well, declared magical by the town's monks, only to find – simply by looking with his own two eyes – the water had escaped through a simple fissure:

"He did everything by incantations; he never worked his intellect. If he had stepped in there and used his eyes, instead of his disordered mind, he could have cured the well by natural means, and then turned it into a miracle in the customary way; but no, he was an old numskull, a magician who believed in his own magic; and no magician can thrive who is handicapped with a superstition like that."

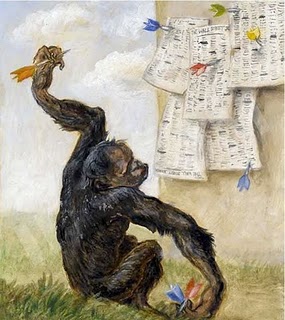

Plus ça change. Even today, a social problem may be defined as a situation in which the real world differs from the theories of intellectuals. And how often do theories stray from the real world? Social psychologist Phillip Tetlock's famous study proved that when grouped together, experts' predictions were worse even than those of dart-throwing monkeys! https://lnkd.in/gAVkgws2.

The number of the world's social problems, then, bears a curious relationship to the number of social theories.

Fortunately, the social sciences supply the antidote to their own folly, and that is through the humility supplied by the study of history. The distinguished British historian Paul Johnson put it well:

"The study of history is a powerful antidote to contemporary arrogance. It is humbling to discover how many of our glib assumptions, which seem to us novel and plausible, have been tested before, not once but many times and in innumerable guises; and discovered to be, at great human cost, wholly false."

No comments:

Post a Comment