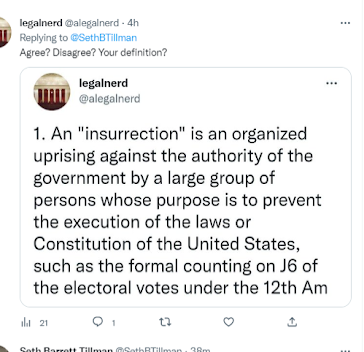

My response:

Your proposed definition of “insurrection” is certainly one possibility. But I wonder if your proposed definition is overbroad?

Under your proposed definition of “insurrection,” in relation to the events involving the American Civil War and Ex parte Merryman in 1861, would not President Lincoln, Generals Winfield Scott, William Keim, and George Cadwalader, Colonels R.M. Lee and Samuel Yohe, and Lieutenant William Abel—all be guilty of insurrection—for preventing the federal courts from hearing habeas corpus applications? And from granting them? See Ex parte Merryman, 17 F. Cas. 144 (1861) (No. 9487) (Taney, C.J., in chambers), <https://tinyurl.com/ms6x7fnd>.

Under your proposed definition, if protesters in a U.S. Senate bathroom block, frustrate, or impede a senator from attending a floor vote, is that an insurrection?

Under your proposed definition, if protesters surround a federal courthouse and impede judges, other courthouse functionaries, and employees, litigants, and other members of the public from ingress and egress, is that an insurrection? Does it matter if some launch pyrotechnics against the building?

Under your proposed definition, if state judges and other court officers establish and put into effect a policy of secreting witnesses and aiding their leaving the state courthouse in order to frustrate their capture by federal immigration officers’ seeking to enforce federal law … is that an insurrection?

I think under your proposed definition, all the defendants in each of my four “hypotheticals” would be in real danger of conviction for insurrection. That’s why I think your definition may be overbroad.

If all that stands in the way of liability in each of these four situations is whether the expressive or political content of the defendants’ actions is valued by the prosecutor, then your definition is problematic. Indeed, each of my “hypotheticals” is based on real-world events. But I do not think any actual prosecutors, state or federal, sought to try any of the real-world defendants for insurrection or anything like insurrection.

You might be better off (using the yardstick of customary rule-of-law norms) with more politically neutral theories of liability: trespass, trespass to chattel, conversion, theft, etc.

On the other hand, if the entire reason one is seeking a conviction for insurrection is to bring about a political disability, then the downside is that the prosecutor will put in motion a series of political and politicized proscriptions and counter-proscriptions. Something like Rome during and after the Second Triumvirate. See generally Josh Chafetz, Impeachment and Assassination, 95 Minn. L. Rev. 347 (2010); Seth Barrett Tillman, Interpreting Precise Constitutional Text: The Argument for a “New” Interpretation of the Incompatibility Clause, the Removal & Disqualification Clause, and the Religious Test Clause–A Response to Professor Josh Chafetz’s Impeachment & Assassination, 61 Clev. St. L. Rev. 285 (2013).

Now, going back to your definition ... I understand the position that the January-6th defendants were “a large group of persons whose purpose [was] to prevent the execution of the law.” But I don’t clearly understand what you mean by an “uprising against the authority of the government.” What precisely do these words mean? What does it mean to participate in an uprising against the “authority of the government,” as opposed to an uprising against the “government” itself?

I also have doubts that inchoate insurrection-related crimes (eg, attempt, conspiracy, solicitation), as opposed to insurrection itself, fall under the aegis of Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment. Is it sensible in regard to political disabilities to move beyond what the plain text permits?

I am so old I remember ... when progressives objected to temporary political disabilities imposed for felonious conduct after conviction in due course of law before a judge with life tenure and a unanimous jury based on evidence proving every element of a criminal offense beyond a reasonable doubt. Yet now, some think it proper to impose permanent political disabilities based on determinations by judges (including even administrative law judges lacking life tenure), absent juries, merely using the ‘more-likely-than-not’ civil standard. Under these conditions, I think the proscriptions and counter-proscriptions of the Second Triumvirate are about the best we can hope for.

Seth Barrett Tillman, ‘A Twitter Exchange on “Insurrection,”’ New Reform Club (Jan. 3, 2023, 6:07 AM), <https://reformclub.blogspot.com/2023/01/an-exchange-on-insurrection.html>;

Twitter: <https://twitter.com/SethBTillman/status/1610232869498281984>;

No comments:

Post a Comment