The Federalist solution: judicial review. Federalist constitutional theory posited that the Supreme Court had the power to judicially review legislation enacted by Congress and signed by the president in order to determine its constitutionality.

In a nutshell, if the Court found that the legislation in question was not constitutional, the legislation would be regarded as null and void. This approach to judicial review was advocated by Alexander Hamilton in The Federalist Papers, specifically No. 78. It also is the theory that was embraced by Federalist Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall in the landmark Supreme Court case of Marbury v. Madison, 5 US 137 (1803). That case has long been considered the key Supreme Court case in the development of the doctrine of judicial review, although it built off earlier case law acknowledging the principle. One of those cases is the 1789 case of Ware v. Hylton. In that case, the Supreme Court struck down a state law under the Supremacy Clause because the state law violated the requirements of a treaty to which the United States was a party.

Jefferson's radicalism and nullification under Calhoun. Jefferson was highly skeptical of the idea of judicial review, and Madison, while originally supporting the idea at the Constitutional Convention, eventually grew skeptical of judicial review as well. During the controversy over the Alien and Sedition Acts, both Jefferson and Madison proposed a different mechanism by which the Constitution's protections could be vindicated in the face of possible abuse by the general government: the doctrine of nullification. Under that theory, a state could nullify constitutionally problematic federal legislation within that state's boundaries, effectively shielding its own state citizens from federal overreach. Sometimes referred to as interposition (from the idea that the state would position itself between its own citizens and the federal government), the Jeffersonian-Madisonian view lived on in American polity well into the 19th century.

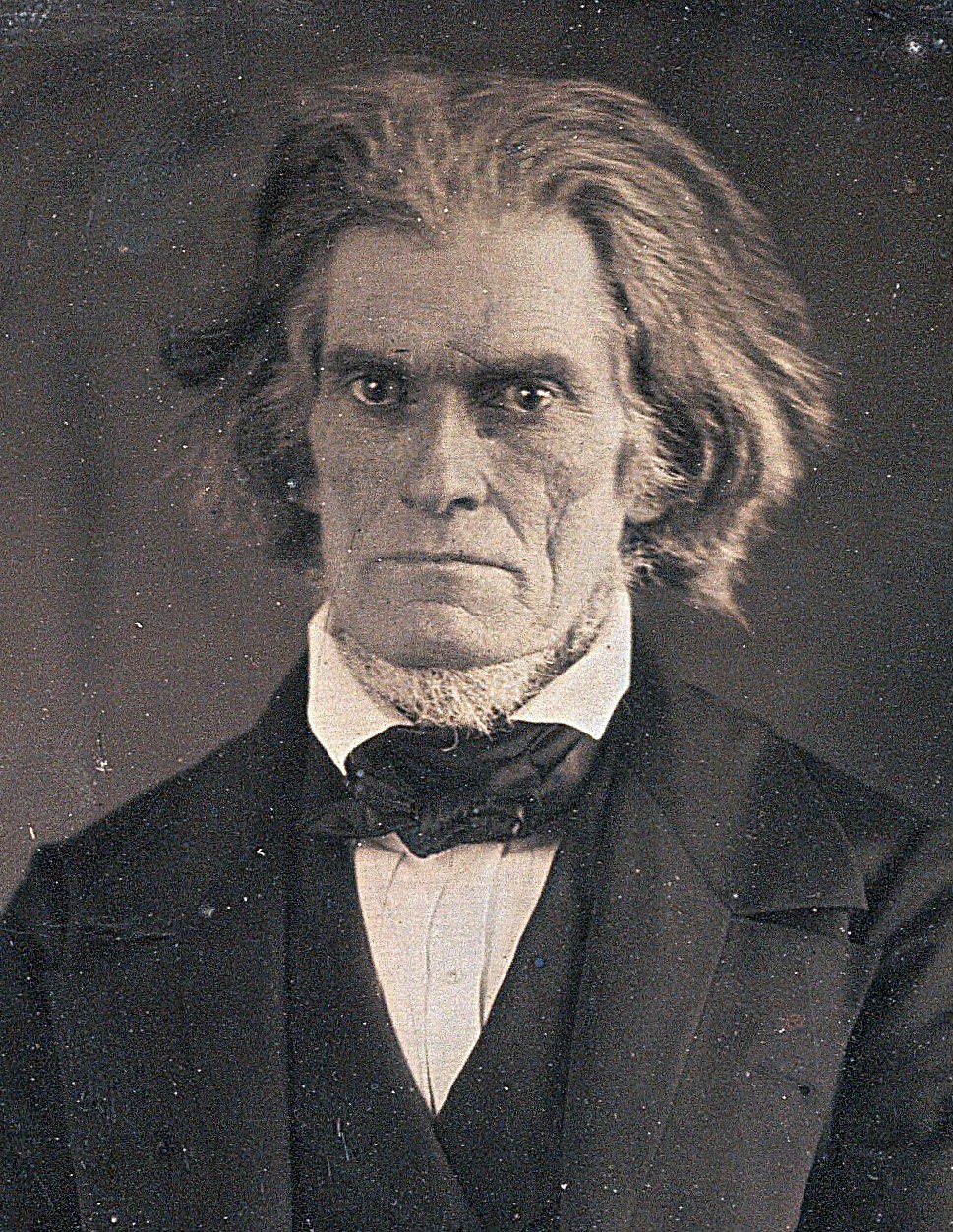

As the Jeffersonian Republicans morphed into the Jacksonian Democrats, the new Democratic Party's southern wing's leader, John C. Calhoun, was an ardent proponent of the idea, and much of Southern constitutional theory, both prior to the Civil War and during the Confederate period, was dominated by the idea. Interestingly enough, prior to the emergence of the Jacksonian Democrats there was a strong view within the Jeffersonian Republican Party in support of the idea of judicial review, despite Jefferson and Madison's misgivings about the doctrine.

St. George Tucker's approach. One Republican proponent of judicial review was Virginia jurist St. George Tucker. Tucker, a federal judge, noted Republican and early proponent of the abolition of slavery, was a major legal theorist in the early Republic, and the author of the first major American edition of Blackstone to be published since Independence. Tucker published his edition of Blackstone in 1803, the same year the Supreme Court decided Marbury v. Madison. In Note D of the first volume of his edition of Blackstone, Tucker makes a strong appeal to the idea of judicial review as a bulwark of constitutional liberty:

The obligation which the constitution imposes upon the judiciary department to support the constitution of the United States, would be nugatory, if it were dependent upon either of the other branches of the government, or in any manner subject to their control, since such control might operate to the destruction, instead of the support, of the constitution. Nor can it escape observation, that to require such an oath on the part of the judges, on the one hand, and yet suppose them bound by acts of the legislature, which may violate the constitution which they have sworn to support, carries with it such a degree of impiety, as well as absurdity, as no man who pays any regard to the obligations of an oath can be supposed either to contend for, or to defend.Specifically taking aim at the constitutionality of the Alien and Sedition Acts, the very acts that led his Republican brethren Jefferson and Madison to propose the radical idea of nullification, St. George Tucker writes a robust defense of the principle of judicial review:

If we consider the nature of the judicial authority, and the manner in which it operates, we shall discover that it cannot, of itself, oppress any individual; for the executive authority must lend it's aid in every instance where oppression can ensue from it's decisions: whilst on the contrary, it's decisions in favour of the citizen are carried into instantaneous effect, by delivering him from the custody and restraint of the executive officer, the moment that an acquittal is pronounced. And herein consists one of the great excellencies of our constitution: that no individual can be oppressed whilst this branch of the government remains independent, and uncorrupted; it being a necessary check upon the encroachments, or usurpations of power, by either of the other. Thus, if the legislature should pass a law dangerous to the liberties of the people, the judiciary are bound to pronounce, not only whether the party accused hath been guilty of any violation of it, but whether such a law be permitted by the constitution. If, for example, a law be passed by congress, prohibiting the free exercise of religion, according to the dictates, or persuasions of a man's own conscience or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people to assemble peaceably, or to keep and bear arms; it would, in any of these cases, be the province of the judiciary to pronounce whether any such act were constitutional, or not; and if not, to acquit the accused from any penalty which might be annexed to the breach of such unconstitutional act. If an individual be persecuted by the executive authority, (as if any alien, the subject of a nation with whom the United States were at that time at peace, had been imprisoned by order of the president under the authority of the alien act, 5 Cong. c. 75) it is then the province of the judiciary to decide whether there be any law that authorises the proceedings against him, and if there be none, to acquit him, not only of the present, but of all future prosecutions for the same cause: or if there be, then to examine it's validity under the constitution, as before-mentioned.Liberty & Union. Why is this important historically? Tucker's work demonstrates the strong appeal during the early Republic of the idea of an independent federal judiciary as a block to constitutional abuses by the federal branches. As the premier defender of Southern Jeffersonianism Clyde Wilson has written of Tucker's views:

One of Tucker’s principal concerns as a legal and political thinker is to affirm the standing of the judiciary as an independent and coequal power with the legislature and executive. This is an American accomplishment to be supported in state and federal governments both. For him the judiciary is the realm where individuals may seek relief from the oppressions of the government. Its power and independence are thus essential.While some of the top-tier Founders within the Republican fold argued for a constitutional theory that would ultimately tear the Union apart, Tucker defended the idea of liberty under, rather than in opposition to, the Union of the States and the federalist system of government established by the Constitution. While Tucker did support the right of States to secede from the Union, that power did not justify nullification or efforts to abandon the role of the federal judiciary as defender of constitutional order.

For Tucker, the Union was grounded in the supremacy of the Constitution and protected by the glory of Anglo-American government: a truly independent judiciary. Tucker's constitutional vision was thus broadly consonant with the Federalist vision enunciated by Marshall. Unlike Jefferson and Madison's proposed solution, which set the stage for a Southern jurisprudence that would eventually justify an illegal attempt at succession, St. George Tucker sought to preserve both liberty and the Union. And did so through the principle of constitutional government & the mechanism of judicial review.

No comments:

Post a Comment